(Dakar) – The Senegalese government’s recent initiative to remove children including those forced to beg by their Quranic teachers from the streets is an important step in reforming a deeply entrenched system of exploitation, Human Rights Watch and the Platform for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights (PPDH), a coalition of 40 Senegalese children’s rights organizations, said today. The groups urged authorities to sustain the momentum with investigations and prosecutions of teachers and others who commit serious violations against children.

During the first half of 2016, at least five children living in residential Quranic schools died, allegedly as a result of beatings meted out by their teachers, known as marabouts, or in traffic accidents while being forced to beg. In 2015 and 2016, dozens of these children, known as talibés, have also been severely beaten, chained, and sexually abused or violently attacked while begging. The deaths and other abuses highlight the urgency with which the government should penalize those responsible for abuse and regulate the traditional Quranic schools, known as daaras.

“Talibés have suffered abuses and dangers that no child should ever have to face,” said Corinne Dufka, West Africa director at Human Rights Watch. “While the government’s recent actions are commendable, removing talibésfrom the streets will not lead to long-term change unless Quranic schools are regulated and offending teachers are held accountable.”

On June 30, 2016, Senegalese President Macky Sall ordered that all street children should be removed, placed in transit centers, and returned to their parents. Anyone forcing them to beg would be fined or imprisoned, he warned. By mid-July, authorities had removed more than 300 children – including many talibés and runaway talibés – from the streets of Dakar. According to local activists and media, several other regions have also begun the initiative, which authorities plan to extend nation-wide.

Though arrests of abusive marabouts have increased slightly over the past year, courts in Senegal have prosecuted only a handful of cases, most involving deaths or the most extreme abuse; forced child begging is almost never prosecuted. Human Rights Watch and PPDH also noted an urgent need for accessible legal services to help talibé victims obtain access to justice.

Among the cases Human Rights Watch documented in 2016:

- In January, a man in Diourbel allegedly lured four talibés to his home and raped them.

- In February, a 9-year-old talibé was beaten to death by his Quranic teacher in the city of Louga. Around the same time, a talibé in the Colobane neighborhood of Dakar was allegedly violently attacked by a stranger in the streets.

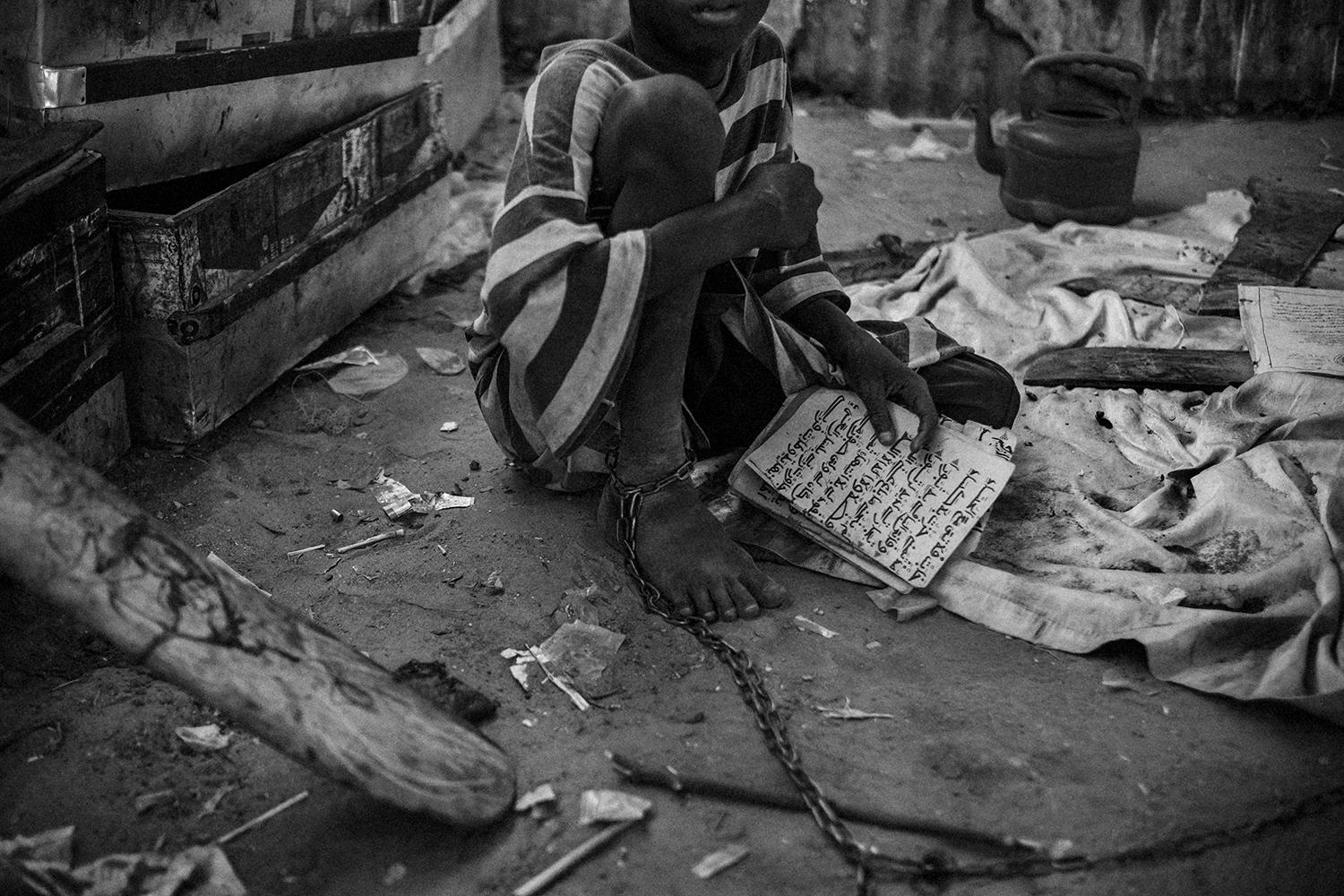

- Also in February, a marabout in Diourbel, arrested for shackling the legs of more than a dozen talibés, was released without charge.

- In March, a Quranic teacher allegedly attempted to bury a talibé in Dakar’s Thiaroye cemetery without legal authorization.

- Also in March, a talibé was allegedly abducted from the streets of Dakar; his whereabouts remain unknown.

- Two talibés died after being hit by cars while begging in the streets of Saint-Louis, in March and April.

- In April, a marabout’s assistant allegedly beat a 7-year-old talibé in Saint-Louis to the point of critical condition.

- In June, a 13-year-old talibé died in the Parcelles Assainies borough of Dakar, allegedly after his marabout severely beat him with a rubber whip for failing to memorize a verse of the Quran.

Human Rights Watch obtained the figures for 2015 and 2016 through detailed analysis of credible media reports on talibé cases, as well as interviews with Senegalese non-governmental organizations, activists, child protection experts, and government officials involved in social services, child protection and anti-trafficking.

From a very young age, tens of thousands of talibé children in Senegal are sent by their parents to live and study at Quranic schools – a practice grounded in religious and cultural tradition. Over the past decade, many Quranic teachers have taken advantage of the unregulated system to exploit and mistreat the children in their care.

Living and sleeping environments in the offending daaras are cramped and unhygienic. Many talibés suffer from severe malnutrition, diseases, and untreated wounds. Long hours on the streets begging put the boys at risk for physical and sexual abuse. Many Quranic teachers regularly administer corporal punishment, and numerous children have died as a result of abuse or neglect, including nine in a 2013 daara fire.

“The death of talibé children as a result of corporal punishment and abuse by some Quranic teachers must no longer remain unpunished,” said Mamadou Wane, president of PPDH. “These killings and other acts of child abuse are the consequences of failing to prosecute perpetrators and imposing weak criminal penalties.”

Human Rights Watch and PPDH have researched and reported on abuses against talibés in Senegal since 2010, documenting scores of cases of forced begging, physical abuse, neglect, and deprivation of their rights to basic health care and education, recreation, and protection against the worst forms of child labor.

Senegal has ratified all major international conventions on children’s rights, and child exploitation and abuse are criminalized under its Penal Code and a 2005 anti-trafficking law. However, the government’s failure to consistently enforce existing law or to pass legislation regulating the Quranic school system has appeared to embolden abusive Quranic teachers.

Despite the recent steps by the Senegalese government and the efforts of local activists, non-governmental organizations, some religious teachers, and the National Task Force Against Human Trafficking (Cellule nationale de lutte contre la traite des personnes, CNLTP) under Senegal’s Ministry of Justice, abuses against talibés remain pervasive. In the 2016 U.S. Trafficking in Persons Report, which ranks countries on their efforts to combat modern-day slavery, Senegal was downgraded from Tier 2 to Tier 2 Watch List. (Countries are ranked from Tier 1, the highest ranking, to Tier 2, Tier 2 Watch List, and finally Tier 3, the lowest and most serious ranking.)

“It should not be only the most extreme cases of talibé deaths that shake the nation and wake up political leaders to the gravity and scale of suffering,” Dufka said. “All children have the right to quality education, a nourishing and healthy environment, a life free from abuse and exploitation, and redress in the case of abuse.”

Senegal should prioritize adoption of the currently stalled draft law to regulate Quranic schools, which would impose universal standards and eliminate begging. The government should also increase training of law enforcement and the judiciary in children’s rights, increase enforcement of existing law, and take steps to address the lack of legal support services for talibé victims, Human Rights Watch and PPDH said.

As the operation to remove the talibés from the streets is carried out, the Senegalese government should ensure that transit centers meet international standards, that the children’s rights are respected at all times, and that efforts to reunite children with their families are adequately supported. Steps should also be taken to guarantee the children’s right to education, including in the transit centers.

“The first priority is enforcement of child protection law; the second is the passage of the draft daara regulation law,” Wane said. “People talk about ‘socio-cultural factors,’ but no culture accepts that children should be treated like slaves.”

State of the Talibé System

Tens of thousands of talibés – typically boys between 5 and 15 – are exploited and mistreated across Senegal. In 2010, Human Rights Watch estimated that at least 50,000 children lived in exploitative and abusive Quranic schools across Senegal’s 14 regions. A 2014 daara mapping by the national anti-trafficking unit found more than 1,000 daaras and 54,000 talibés in the Dakar region alone, of whom more than 30,000 were forced to beg daily. A mapping of Senegal’s northern Saint-Louis department in 2016 counted more than 200 daaras and 14,000 talibés, with more than 9,000 compelled to beg, a researcher involved in the mapping reported to Human Rights Watch, just before President Sall’s June order to halt forced begging.

Tens of thousands of talibés – typically boys between 5 and 15 – are exploited and mistreated across Senegal. In 2010, Human Rights Watch estimated that at least 50,000 children lived in exploitative and abusive Quranic schools across Senegal’s 14 regions. A 2014 daara mapping by the national anti-trafficking unit found more than 1,000 daaras and 54,000 talibés in the Dakar region alone, of whom more than 30,000 were forced to beg daily. A mapping of Senegal’s northern Saint-Louis department in 2016 counted more than 200 daaras and 14,000 talibés, with more than 9,000 compelled to beg, a researcher involved in the mapping reported to Human Rights Watch, just before President Sall’s June order to halt forced begging.

By no means is every daara exploitative. A number of Quranic teachers champion the movement to improve the system and protecting talibé rights. However, many others have operated as businesses under the pretext of teaching the Quran.

Many Quranic teachers set up these “schools” in abandoned or run-down buildings, typically in conditions of extreme squalor. Most talibés sleep on the floor, unprotected from malaria-carrying mosquitos. The children’s days consist of Quranic studies alternated with up to 10 hours of forced begging on the streets for “alms” – food or money. Few talibésreceive health care or education beyond memorizing the Quran. Lessons are often punctuated by corporal punishment, and failure to bring back daily quotas of money from 500 to 2,000 francs CFA (US$1 to US$4) can result in severe beatings.

According to a UN expert on human trafficking in Senegal, the estimated 30,000 talibés begging in Dakar alone have generated an estimated 5 billion francs CFA (US$8 million) per year for Quranic teachers.

“We haven’t collected enough money yet, so we can’t go back [to the daara],” two young talibés, wandering late at night on the streets of Dakar, told Human Rights Watch in early 2016. The boys, who did not know their ages, were from the far-south region of Kolda and could not explain why they had been taken north to Dakar.

While the vast majority of talibés in the country are Senegalese, many are sent to live with Quranic teachers in cities far from their home community or region. Hundreds are also trafficked by marabouts to Senegal each year from neighboring countries. From March 2015 to May 2016, local groups and media reported instances in which more than 200 talibé children were found in other countries or intercepted while attempting to cross borders. They included more than 100 Senegalese talibés found in the Gambia, as well as at least 50 children from Guinea-Bissau and 60 from Guinea traveling to Senegal.

In addition, some 90 of the more than 300 children, including talibés, removed from the streets of Dakar in early July 2016 were from other countries including Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Gambia, and Mali, according to local groups.

While local children’s rights activists believe the number of talibés subjected to forced begging continues to increase, they also note a greater willingness by local residents and the media to report cases of abuse, and by the police and government officials to initiate investigations.

“Today, even if the State doesn’t want to advance definitively, the population will denounce and say that we can no longer mistreat the talibé children with impunity,” said Abdou Fodé Sow, member of PPDH and coordinator for Senegal’s Departmental Child Protection Committee (Comité Départemental de Protection de l’Enfant, CDPE) in Pikine, Dakar. “More and more Quranic teachers are being brought to the police stations. Now, anywhere there is a CDPE in Senegal, if a child is mistreated or beaten to death, the CDPE will bring the case to the prefect or sub-prefect.”

Issa Kouyaté, a child rights activist who runs a shelter called Maison de le Gare in the northern city of Saint-Louis, also noted improvement at the police level. “There has been a change,” said Kouyaté. “They used to see children sleeping in the streets and did nothing; now they call me all the time.”

Following the president’s recent ban on begging, Senegalese activists and media reported that fewer talibésappeared to be begging in the streets of Dakar and Saint-Louis. However, some warned that a number of Quranic teachers are now simply altering the times they send talibés out to beg, in order avoid police patrols.

Serious Abuses Against Talibés

In addition to the ubiquitous forced begging, Human Rights Watch documented 20 cases during 2015 and 2016 in which talibé children were hurt, mistreated, or killed. These include cases of physical abuse, attacks, rape, traffic accidents, and death due to assault or battery. Seven talibés are known to have died during this period.

In addition to the ubiquitous forced begging, Human Rights Watch documented 20 cases during 2015 and 2016 in which talibé children were hurt, mistreated, or killed. These include cases of physical abuse, attacks, rape, traffic accidents, and death due to assault or battery. Seven talibés are known to have died during this period.

In 10 cases, teachers allegedly committed the abuse, including four cases in which talibés died allegedly as a result of severe beatings. Six cases involved chaining or physical abuse of at least 15 boys.

The remaining 10 incidents occurred outside the school while the boys were begging, or in one case when a stranger entered a Quranic school. These include five cases of rape or sexual abuse; two violent attacks on talibés, one leading to the child’s death; two car accidents in which the talibés were killed; and one alleged abduction from the streets of Dakar.

The majority of incidents took place in the Saint-Louis and Dakar regions, followed by some in Diourbel and Louga.

Beating, Chaining, and Deaths

In the most recent documented case of abuse in a Quranic school, in June 2016, police officers in Saint-Louis discovered a 12-year-old talibé chained to the wall.

“The police called me, and they were in the middle of breaking the chains when I arrived,” said Kouyaté, the shelter director. “I saw the boy with his two feet chained, facing the wall, holding a Quran. He said he was chained because he hadn’t found money, and he had also run away before. The marabout’s assistant did this so he could no longer run away.” The police investigation was dropped after the assistant fled the daara. The head marabout was not arrested.

Also in June, a 13-year-old talibé from the Parcelles Assainies borough of Dakar died after his teacher severely beat him with a rubber whip, twice in one day, for failing to memorize a verse of the Quran. The teacher, who had attempted to take the child’s body to Touba for burial, was intercepted by the Touba police and arrested.

In April 2016, a 7-year-old talibé in Saint-Louis was severely beaten with a rubber whip, allegedly by the marabout’s son, who served as his assistant. The head marabout was not held accountable, and police released the assistant with instructions not to beat children any more, a local activist told Human Rights Watch.

In April 2016, a Quranic teacher was arrested after illegally burying a talibé in Dakar’s Thiaroye cemetery in March with a falsified death certificate. The child’s father, who participated in the burial, later reported his son’s death to the police, noting that he had seen blood in the mouth and marks on the child’s body suggesting abuse. The body was then exhumed by order of the prosecutor, an autopsy was performed, and the teacher and gravedigger were arrested and referred to the prosecutor. Investigation is ongoing.

In February 2016, the police rescued about a dozen children with their legs shackled by iron bars from a daara in Diourbel, 130 kilometers from Dakar. The boys, from 6 to 14 years old, were taken to the police station, where metalworkers were called to remove the bars. A local journalist who witnessed the scene provided a photo of the shackled children to Human Rights Watch.

However, the prosecutor ultimately dropped the investigation. “After his arrest by the Diourbel police, the marabout was released following intense lobbying by certain key figures, religious and non-religious,” said Mamadou Ndiaye, head of the Diourbel CDPE.

Earlier in February, a teacher beat a 9-year-old talibé to death in Louga, 180 kilometers from Dakar. A medical certificate identified the cause of death, and the Quranic teacher was arrested, tried, and sentenced to two years in prison.

In late 2015, two cases of abuse by Quranic teachers occurred in Saint-Louis. In November, the police found a talibé with his feet chained; in August, a teacher horribly beat a talibé no older than 8. Both cases resulted in arrests, convictions, and several months in jail. Kouyaté, who was called to help in both incidents, described what happened to the younger talibé:

He had left to go beg, but he fell asleep waiting for food. He woke up very late and it was morning, and he was afraid to return to the daara... When he did return, they beat him with a rubber whip made from a tire. It gave him serious infections on his back. After three days of rest, the marabout sent him back out to beg. He was sick and in terrible shape, but they sent him out to beg anyway, because he had to reimburse the days he had run away and the days he had rested at the daara.

Today, we have identified three steps to achieving justice for talibés. The first step is the local neighborhood. The population used to say that cases of mistreatment were not serious if nobody died, but now everyone denounces them.Second step, at the police level: previously they would call the Quranic teacher and discuss with him, saying it must have simply been an accident. But today, each time a child is mistreated or beaten to death, the prefect is notified and he asks the police to pursue the case. Now the prefecture and the police work together to advance justice.The third step is the prosecutor, but he is not always comfortable interpreting the law due to the pressure he experiences. The challenge now is, how to give the judiciary more liberty to freely carry out its duties?

A social worker for a region in southern Senegal echoed the concern about a lack of response from many local prosecutors.

I see many, many instances of mistreatment – children less than 5 years old in the streets, with injuries or sicknesses, dirty and not well dressed. …Every day I denounce this; I speak of it in meetings, to the police, I speak of it everywhere I go. I send reports to the prosecutor each week, but the cases are not pursued.

Representatives of the Justice Ministry’s anti-trafficking task force, CNLTP, also spoke to Human Rights Watch of their concerns about what they characterized as the unwillingness of some prosecutors to initiate investigations and prosecutions against Quranic teachers, for both abuse and forced begging. One representative said CNLTP is often “surprised” at the number of times abusive Quranic teachers are released or acquitted, despite strong cases against them.

The CNLTP representative urged prosecutors to be more proactive in protecting children. “It’s the prosecutor who should pursue [the case], if he sees something abnormal,” she said. “He should not have to wait for non-governmental organizations to denounce a case.”

Wavering Political Will

After the spate of abuses against talibés were reported in the Senegalese media in early 2016, several political leaders denounced the practice and took measures to address it. In May, President Macky Sall made a statement before the Council of Ministers reiterating the need to accelerate passage of the draft daara regulation law. This followed statements made by mayors of two Dakar districts, Medina and Gueule-Tapée-Fass-Colobane, publicly banning begging and exploitation of talibé children. A third mayor from the Thiès region urged religious leaders to “serve” their talibés rather than exploit them.

After the spate of abuses against talibés were reported in the Senegalese media in early 2016, several political leaders denounced the practice and took measures to address it. In May, President Macky Sall made a statement before the Council of Ministers reiterating the need to accelerate passage of the draft daara regulation law. This followed statements made by mayors of two Dakar districts, Medina and Gueule-Tapée-Fass-Colobane, publicly banning begging and exploitation of talibé children. A third mayor from the Thiès region urged religious leaders to “serve” their talibés rather than exploit them.

Most recently, in late June, President Sall announced the order for the removal of all street children, beginning with Dakar. He stated that those forcing the children to beg would be fined or imprisoned.

The rhetorical attention to the problem, while positive, was reminiscent of the promises that followed the 2013 deaths of nine talibés in Dakar, locked in their Medina daara overnight when a fire burned it to the ground. Though the incident sparked national outrage and led to a number of government promises, few have been fulfilled. There were no prosecutions following the Medina fire.

That said, the Senegalese government has taken several steps over the past year to address the issue, including the current initiative to remove children, including talibés, from the streets, a draft bill that would create an independent Children’s Ombudsman, and the finalization of a draft Children’s Code soon to be submitted to parliament. In late 2015, the Interior Ministry announced that, in addition to the sole existing Juvenile Justice Unit (Brigade des Mineurs) at the central police station of Dakar, special offices to handle cases involving children would be installed in all other police stations.

In addition, the national anti-trafficking task force periodically trains police and members of the judiciary on how to prevent human trafficking. The task force has also developed a database to collect information on trafficking-related cases around the country, though training of judicial personnel on use of the database is progressing slowly.

However, there has been slow progress in ensuring a much-needed regulatory framework for Senegal’s Quranic schools. A law drafted in 2013 would require all such schools to adhere to minimum standards, submit to state inspections, and eliminate begging. Due to an extended amendment process, the law has yet to be presented to the National Assembly. The law is currently under review by the Ministry of Education and the national federation of Quranic teachers.

Senegal is party to the United Nation’s Convention on the Rights of the Child, the African Charter on the Rights and Welfare of the Child, and all major international and regional treaties guaranteeing protections against child labor and trafficking. International law also affords children the rights to health, physical development, education, and recreation. The state, parents, and any de facto guardians are obligated to fulfill these rights.

In January 2016, Senegal went under a periodic review by the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which noted a number of concerns regarding talibé children. In mid-2015, the African Committee of Experts on the Rights and Welfare of the Child (ACERWC) had concluded that Senegal had violated numerous provisions of the African Children’s Charter.

Both bodies issued strong statements on the need to enforce existing laws, investigate and prosecute those accused of abuse, and remove talibés from detrimental and abusive environments.

Need for Legal Aid Services

Senegalese child rights activists consistently identified the lack of legal support services for the children and their parents as a major barrier to justice for talibé who suffer abuses.

Senegalese child rights activists consistently identified the lack of legal support services for the children and their parents as a major barrier to justice for talibé who suffer abuses.

Talibé victims have three main options to seek justice. State prosecutors can open an investigation; parents can file a complaint; or a non-profit or social services institution can file a complaint on the child’s behalf, in the absence of family members.

Few prosecutors open such investigations on their own initiative. In a number of major cases, notably those involving talibé deaths, parents have filed complaints with the police and pursued the case in court. However, thousands of talibés live in Quranic schools far from home, often out of touch with family. Only occasionally will a complaint be filed on their behalf by the regional offices of the Justice Ministry’s social services agency, AEMO, and much more rarely by local non-governmental groups.

Unfortunately, AEMO offices for social services – present in Senegal’s in regional capitals and often staffed by just two or three people – lack the capacity to handle a high volume of cases, local activists say. As a result, only the most severe cases are pursued.

While the AEMO representative for Saint-Louis said he has encountered and reported a number of recent cases of abuse, the coordinator for another region said that he has only handled cases of about 15 runaways and not abuse.

Many non-governmental and non-profit organizations lack the legal training or funding to regularly provide legal support. A report by the anti-trafficking unit after a visit to Saint-Louis stated that most groups do not make use of the opportunity offered to them by law to file complaints on behalf of victims in order to allow prosecutors to open criminal investigations.

Considering the gap in legal services for talibés, Human Rights Watch encourages donors and the Senegalese government to fund increased personnel and training for AEMO social services offices, as well as to develop and fund legal clinics in each region of Senegal to help talibé child victims file judicial complaints and appeals.

The lack of consolidated documentation of police incidents, court cases, and illegal border crossings involving talibés also undercuts activists’ efforts to highlight the urgency of passing the draft daara regulation law. Without updated, comprehensive information that is widely shared, the scale of the problem will remain unclear to authorities.

Recommendations

To the Senegalese Government

On the Application of Laws Against Forced Begging and Abuse

- As the initiative to remove children from the streets is carried out, ensure that their rights are respected during the transition, that the transit centers are monitored and adhere to international standards, and that children are swiftly reunited with their families;

- Enforce the anti-trafficking law (no. 2005-06) by ensuring that police, prosecutors, and social services report, initiate, and pursue cases of children forced to beg; and

- Enforce article 298 of the penal code, which criminalizes the physical abuse and neglect of children, by investigating and holding to account all those who physically abuse talibés, including Quranic teachers.

On the Regulation of Quranic Schools

- Accelerate and conclude review of the draft law for regulating Quranic schools, in order to submit the law to the National Assembly as soon as possible;

- Increase funding for the Daara Inspectorate within the Education Ministry, with a view to shutting down schools that violate children’s rights and supporting placement of children from abusive schools in temporary shelters while their families are traced; and

- Implement the Interior Ministry’s plan to install offices dealing with children and minors in each regional police station, and ensure that each office has adequate funding and personnel trained to protect children to fulfill its mandate.

On Coordination Among Actors Working on Talibés

- Consider creating a national talibé working group, headed by the anti-trafficking task force and the Ministry of Family, Women, and Children, to include other relevant government ministries, representatives of Quranic teachers’ organizations, activists and non-governmental groups, and UN and other international organizations;

- To all groups and entities listed above: Share information to avoid duplication of efforts, particularly in regard to mappings of Quranic schools, which are being carried out in the same locations by multiple parties; and

- Consider supporting relevant authorities, such as the national anti-trafficking task force and the Directorate for the Protection of the Rights of Children and other Vulnerable Groups within the Ministry of Family, Women, and Children, to begin periodically collecting information to document regional police and court cases involving talibé children, including physical abuse and sexual assault. This would build on the anti-trafficking unit’s database of human trafficking cases, which does not include other abuses against talibés. Information collected should be shared among all actors.

To International Partners and the Senegalese Government

- Increase funding for and support to structures and organizations providing legal assistance to talibé children who are victims of abuse, exploitation, and trafficking;

- Consider increasing support and training for regional offices of the Justice Ministry’s social services agency, Action Educative en Milieu Ouvert (AEMO); and

- Consider providing increased support to the Justice Ministry’s anti-trafficking task force, and to the children’s rights directorate within the Ministry of Family, Women, and Children.

No comments:

Post a Comment